From the first three blog posts in this series, we learned that Mary Ann Lippitt was a steadfast advocate for Deaf education and supported the founding of Rhode Island School for the Deaf (RISD) in 1876. Specifically, Mary Ann advocated for oralist education, which prioritized Deaf students’ ability to “fit in” to the hearing society. Jeanie Lippitt, who became deaf at age four, was seen as successful in that regard by communicating through lipreading and speaking.

Still, our most recent post highlighted a different perspective than assimilation: being Deaf is a cultural-linguistic identity and needs to be embraced as part of human diversity. To this day, discrimination against Deaf people persists and education for Deaf children is far from equitable. Oralism continues to play a big role in both issues. This post will offer a closer look at the history and repercussions of the oralist movement, with its crucial figure being one of Jeanie Lippitt’s voice teachers.

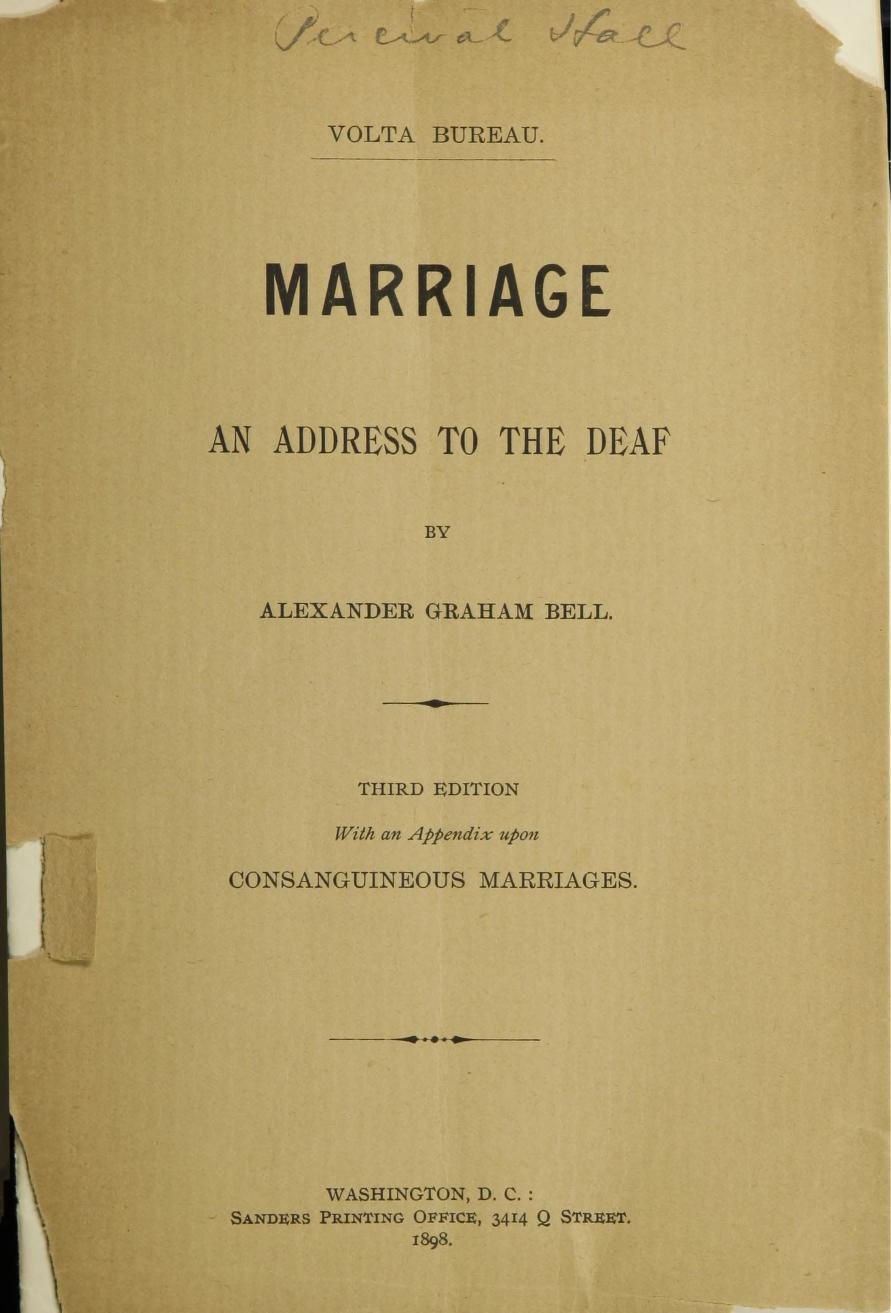

Alexander Graham Bell and Oralism in America

Alexander Graham Bell, one of Jeanie’s voice teachers, is a significant figure in Deaf history. Bell’s advancement of the oralism movement, in which the Lippitts were involved, left a complicated legacy of oppression against the Deaf community.

Bell, born in 1847, was the son of a deaf mother and a father dedicated to speech training. His father created a system called Visible Speech and used it to teach deaf people to speak (Greenwald 2024). Alexander followed his father’s career in deaf education, first teaching Visible Speech, and then eventually opening his own school to give private lessons in speech and lipreading to deaf students. One of these students was Jeanie Lippitt (Soules 2024).

Bell's efforts to promote oralism at a national level paralleled Mary Ann Lippitt's campaign to establish oralist schools in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. At the core of Bell’s push for oralism was his concern that “a [D]eaf variety of the human race would form at a critical period in American history” (Greenwald 2024). From teaching Deaf people to speak to advocating for banning the intermarriage of Deaf people, Bell became more and more invested in erasing their Deafness rather than advocating for their welfare. Bell's eugenic agenda situated itself in the broader eugenics movement at the time, and it poignantly illustrates how Deaf people were often “the canary in the coal mine of social engineering” (Bauman and Murray 2012).

Oralism on the Global Stage

In 1876, Mary Ann Lippitt founded the Rhode Island School for the Deaf in Providence, while Oralism also was gaining prominence on the other side of the Atlantic. In 1880, the International Congress on Education of the Deaf (ICED) in Milan declared that oralist education was superior to sign language education and passed a resolution banning the use of sign language in Deaf schools. Since then, for multiple generations of Deaf people around the world, oralism was heartily embraced by social elites and idealistic hearing educators in Europe and America. Yet, its glorified promises of social integration covered that Deaf people were not considered equals unless they could overcome deafness with oral communication (Gallaudet 1881).

This ban continued until the 1960s, when Deaf rights advocacy finally managed to break through and gradually shift the public perception of Deafness. At last, in 2010 in Vancouver, the 21st ICED rejected all resolutions from 1880. It stated that "the influence of Milan dominated the field for more than 80 years. Although the situation has improved since the 1960s, the lost opportunities for optimum development for generations of Deaf individuals are undeniable and can never be atoned for” (Moores 2010). The conference called upon all nations to “remember history and ensure that educational programs accept and respect all languages and forms of communication” (ibid).

As students of ASL and Deaf Culture, we have humbly put together this series of blogs to introduce the history and raise awareness for sign languages and Deaf rights. While we cannot tell what the Lippitts would have done had Jeanie lived today, we know that much progress has been made in educational access and opportunities for Deaf children, building on the legacy of Mary Ann and Jeanie Lippitt.

Click #DeafEducation to find all the posts in this series.

Guest bloggers: Irene Zhiyi Chen AB Candidate ’25 Theatre Arts and Performance Studies and Education Studies, Brown University and Eric Hadley AB Candidate '26 Theatre Arts & Performance Studies and Certificate in Intercultural Competence, Brown University

References

Bauman, H-Dirksen L. and Murray, Joseph J. 2012. “Deaf Studies in the 21st Century: “Deaf-gain” and the Future of Human Diversity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education, Vol. 2, edited by Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer. Oxford Library of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195390032.013.0014.

Gallaudet, Edward M. 1881. “The Milan Convention.” American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb, 26 (1): 1-16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44461114.

Greenwald, Brian H. “Alexander Graham Bell and His Role in Oral Education.” Disability History Museum, accessed on August 15, 2024. https://www.disabilitymuseum.org/dhm/edu/essay.html?id=.

Moores, Donald. F. 2010. “Partners in Progress: The 21st International Congress on Education of the Deaf and the Repudiation of the 1880 Congress of Milan.” American Annals of the Deaf, 155 (3):309-310. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2010.0016.

Soules, Rebecca. “Her Mother’s Triumph: Jeanie Lippitt Weeden.” Rhode Tour, accessed on August 15, 2024. https://rhodetour.org/items/show/2.

Comments